On Perfectionism and Poets

I was on the poetry slam team in high school, where my ideas were being encouraged and raised up into what the spoken word community called “brave new voices.” I took that encouragement and wrote about what I felt deep inside me: what it felt like to be called a chink or a coconut, what it felt like to never know the land or the people that my parents came from, what it felt like to feel a connection to others like me, a child of immigrants.

In art school, hell-bent that the merit of my talent would make me an overnight sensation, writing became a competition. At the end of every semester, the instructors would put our final pieces in a pile to be read to the workshop. If you were read last or near to last, it was an unspoken rule that your piece was “the best.” I was always read last, or near to last. After that, I would not write or share my writing unless it was to be read last, unless it would lead to my becoming The Next Big Thing.

Upon graduation, jaded by the recession and the mountain of debt I’d graduated into, I entered Corporate America, analyzing market trends for a pharmaceutical distribution company. I was one of hundreds in a gray cube, working my tail off to be noticed by my bosses. For what? I wasn’t entirely sure. Sometimes it was a pat on the back. Other times it was a good performance review and a pay raise. My purpose became even more blurred each day I clocked in.

In the evenings, I would send my work to editors who were looking for something specific, and who'd rejected the work without explanation. I took those rejections personally, and I began to believe that poetry and literary writing was a space that was dead. I began to believe it was a space meant for Ivy League MFA graduates, a club for the elite that sat around praising their own work. It was a space that I thought was lost in stuffy literary magazines that never accepted anyone of color. A space that didn’t create careers. A space that’s become “a saturated market,” a place too full to accept anyone new.

“Imprisoned by my perfectionism and the expectations for assimilation I put on myself, my stories and poetry sat inside me waiting for their release.”

I was stuck in a system, one that keeps the mind occupied on a prize you can’t quite pinpoint. A system that directs you away from your true desires and longings by working you to the bone. I was focusing on what I thought I wanted: material wealth, outside validation, and career climbing. To look the part, I wore pencil-skirts, collared shirts, and too much eyeliner, but inside I was naked, crumpled into a ball on the floor, with puffy eyes and barely able to breathe.

Imprisoned by my perfectionism and the expectations for assimilation I put on myself, my stories and poetry sat inside me waiting for their release. I began to believe that I had nothing of real value to say, trusting only the work that instructors had once praised or producing reports demanded by bosses. My opinions began to fade, a fog blurring my perspective. I felt that everything had already been said. That my place was to be another worker bee and pay off my giant, private art school debt and get married and be like this forever.

I became afraid to speak my mind, whatever was left of it. I stopped writing. When I did write, I never shared it with anyone for fear of being disliked. I began to believe that what I had taught myself, that my voice did not matter, was true. I believed no one would listen.

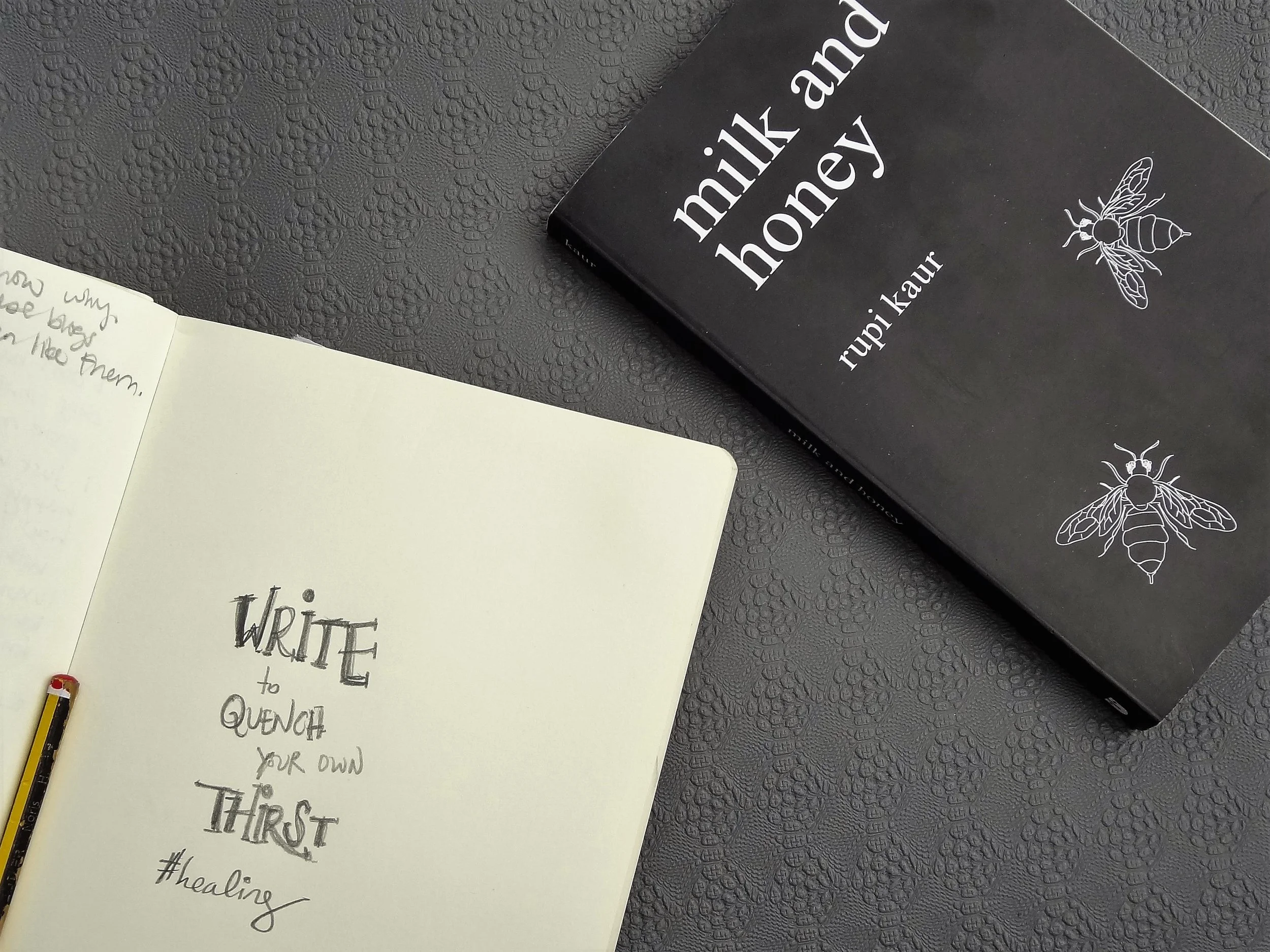

After years of this, I broke down after a yin yoga class that my sister taught. I just sat in her studio and cried. After having realized I had lost myself, weeping was all that was left to do. When it was over, my sister handed me a book that had been handed to her by another woman, “You're going to love this. It will heal you.”

It was Rupi Kaur's Milk and Honey. I read it in one hour (I would later read it over and over again, tattooing the lines into my memory). And that day, I passed it to another friend. We looked up Rupi Kaur and swallowed the FAQ section of her website whole. I wept at the following passage:

our trauma escapes the confines of our own times. we’re not just healing from what’s been inflicted onto us as children. my experiences have happened to my mother and her mother and her mother before that. it is generations of pain embedded into our souls.

It was this passage that solidified an instinct I'd had when I started writing in high school and had lost under the cloud of adulthood: as a woman of color, I have generations of messages I carry inside me, caged and waiting.

Writing our own stories and the stories of our mothers and grandmothers and their grandmothers exorcises those ghosts out from inside us. It unleashes the power those stories hold. It is a rebellion against a system that wants you to believe that you aren’t enough, that you aren’t valued or heard or seen.

“You’re going to love this. It will heal you.”

This is why we need to keep reading each other's work. This is why we need to motivate ourselves to keep writing—it’s an act of survival.

Rupi Kaur self-published and caught the eye of a publisher after so many people noticed her without their help. Nayirrah Waheed, a poet of color who has also self-published on Instagram, has 307, 000 followers and hundreds of others quoting and reposting her works across the network.

In an interview with ezibota.com, Waheed spoke on the strength it takes to be a writer:

I write because I need to be honest, so for me, writing/art is the place I get to be most honest. Honesty is what’s probing me to write. Sometimes I am afraid but my spirit says write it. I have to rise up in that moment and write. I have to be that honest, that sharp, that biting. My soul knows why it needs it to be this way. If this is what my soul wants me to say, this is what I’m going to say. It takes a lot of courage to stand directly with yourself.

A poet who goes by the name Camillea, self-publishes her poems on Tumblr and GoodReads.com. Her poem “To the Colonized Woman of my Bloodline” made me feel like she reached her long, beautiful fingers into my soul and arranged the words beautifully into painting, confirming what Kaur said about writing for the generations before us.

About her process of sharing her work, Camillea says, “As a writer, I don’t make money for the things I create. All my poems and two of my chapbooks are available to you for free.”

These women didn’t listen to the expectations of others. They did not put in the hours studying someone else's work to see if they fit within it. Instead, they spent the time constructing their own creations. They have carved space into a place that once been seemingly “saturated." They didn’t hold themselves back and shared the hell out of their work in their own way, not someone else’s.

We cannot let our perfectionism, our depression, our anxiety, our mania, nor the expectations put upon by ourselves and the system get in the way of what we need to say. We need to write. Writing keeps the stories from rotting our insides, as it pines at its imprisoned walls to get out. Let them out and don't be afraid to share them. We need to write to keep ourselves awake and to wake others up.

Hemingway was famous for saying, “There's nothing to writing. All you do is sit at a typewriter and bleed.” What he failed to understand was that yes, we need to bleed to write, but we also need to heal.

The healing is what I find so beautiful about these poets, these women warriors bleeding and healing themselves on the page.

So instead of living up to someone else's standards of the way I should write, I'm going to keep honing my craft. Honing it until it communicates exactly what I need it to, exactly what my ancestors need to me to say, exactly what I want to say in gratitude to them. I will write until my fingers bleed and heal themselves again, until the pounding in my soul is heard like marching drum in the distance.

Teresa Mupas Purugganan lives with the smell of ginger root in her nostrils and her mother's stories in her soul. She is a wanderer of planet earth, a writer and poet, yogini, auntie, sister, cousin, daughter, and teacher. Born in the shower of a tidy suburb of Detroit to a set of hardworking Filipino parents, she now lives off the Atlantic coast of Northern Spain and once lived in a crowded, hot city in central Thailand. She daydreams, and often wonders what the world would be like if we all unleashed our inner artist souls and danced to the rhythm's of nature.

Follow her on instagram @theblackbirdexperiment.

Website: www.teresamupas.com